Say My Name

Photography is a visual medium that primarily communicates through images, yet the titles we give our photographs play a significant role in how viewers interpret and engage with our work. This relationship between image and text creates a fascinating dynamic that has evolved throughout photography's history and continues to shape our experience of photographs today.

The Historical Evolution of Photographic Titles

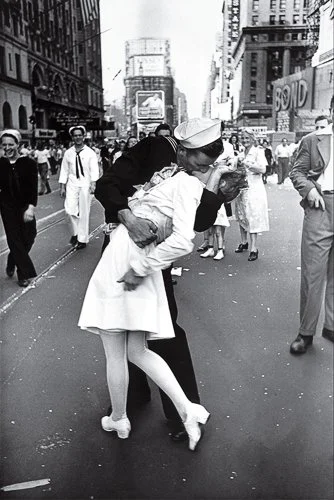

Since the inception of photography in the early 19th century, the practice of titling photographs has undergone numerous transformations. In the medium's early days, titles were predominantly functional, often simply identifying the subject matter and date of creation. For instance, the title "V-J Day in Times Square" (1945) by Alfred Eisenstaedt straightforwardly identifies the time and place of the iconic image.

As photography developed as an artistic medium, approaches to titling became more varied and conceptually sophisticated. By the mid-20th century, the relationship between image and title had become a fertile area for creative experimentation. In the 1960s, photographers frequently employed symbolic, psychological, and mystical titles that reflected the countercultural zeitgeist, titles such as “Quest of Continual Becoming” (1965) and “Apocalypse II” (1967). Remember, we are talking about the Sixties, and most people were a little bit high.

This period also saw the emergence of a trend that would become particularly significant: the deliberate use of "Untitled" as a specific title choice. Unlike simply neglecting to name an image, photographers consciously choose this option to indicate that viewers should interpret the images without textual guidance. This practice highlights a fundamental tension in photography: the desire for images to speak for themselves versus the impulse to guide interpretation through language.

Approaches to Titling in Contemporary Photography

Several distinct approaches to titling have emerged in modern photographic practice. Each serves a different purpose and reflects particular philosophies about the relationship between image and text.

1. Descriptive Titles

The most straightforward approach is the descriptive title, which identifies the subject, location, or circumstances of the photograph. Titles like Ansel Adams's "Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico" (1941) follow the classic convention of naming the subject and adding the date of creation. This approach prioritises clarity and contextual information over interpretive guidance.

Many photographers find that simple, descriptive titles work best for landscape, wildlife, and documentary photography. They effectively convey factual information that supports the viewer's understanding without overshadowing the visual impact.

2. Titles as 'Instructions for Use'

An intriguing way to understand photographic titles is to view them as similar to video game loading screens—brief moments where the creator can provide "instructions for use" to the viewer. Like a loading screen that sets expectations and provides context for the gameplay to follow, a photograph's title creates a frame through which the viewer approaches the image.

This comparison is particularly apt in our digital age. Just as gamers appreciate how their own in-game photographs appear as loading screens in games like Fallout 76, creating a sense of scrapbook memories, a thoughtful title can transform how viewers engage with a picture, providing an entry point into the experience the photographer wishes to convey. Consider how different titles might affect your perception of the same image:

A photograph of a tulip could be titled simply "Tulip" (descriptive)

The same image, titled "The Right To Be An Individual", transforms into a statement about uniqueness and nonconformity

Left untitled, viewers might focus more on formal qualities like colour and composition

Each approach provides different "instructions" for experiencing the image, without necessarily determining a single correct interpretation.

3. Poetic and Conceptual Titles

A more interpretive approach uses titles to suggest mood, emotions, or concepts that extend beyond what is overtly visible in the image. In this category, photographers create titles that function as an artistic extension of the image itself, adding layers of meaning that might otherwise remain obscure.

Research suggests that conceptual titles significantly increase viewer interest and appreciation of photographs. One study found that pictures paired with their original conceptual titles received higher ratings than the same images paired with merely plausible or random titles.

Examples of conceptual titles include "Presence of the Enigma" for a photograph of a woman on a street, which creates an association between the image and the concept of mystery. Such titles invite viewers to ponder questions like: Is this particular woman an enigma? Are women generally enigmatic? Am I going to get in trouble for even asking this? The title opens interpretive possibilities that might not arise from the image alone.

4. Untitled Works

Many photographers deliberately leave their works untitled, allowing the images to stand or fall purely on their merits. This approach reflects a philosophical stance that photographs should convey their meaning directly without requiring verbal mediation.

As one photographer noted, "I've wanted to reach a point where my photographs are strong enough to stand alone, without being propped up by words to try to make them more interesting. Plus, I like to leave the interpretation up to the viewer rather than guide them down a certain avenue of thinking and responding."

Some of the most significant photographic projects in history have deliberately gone untitled. Cindy Sherman's groundbreaking series "Untitled Film Stills" (1977) consists of 70 black-and-white images in which Sherman poses as various fictional female characters from imaginary films. The absence of specific titles invites viewers to create their own narratives around the photos.

5. Numerical Systems

Some photographers employ numerical coding systems, particularly when working with multiple cameras or film types. This approach creates an organisational framework without imposing interpretive guidance. However, such systems can become unwieldy when working with numerous equipment combinations.

The Function of Titles in Photography

Titles serve multiple functions beyond merely identifying an image. Understanding these functions can help photographers make more intentional decisions about how to name their work.

Guiding Interpretation: Titles direct viewers' attention to particular aspects of an image, influencing how they perceive and interpret what they see. The French literary theorist Roland Barthes described this function as "anchorage," where the text "directs the reader through the signifiers of the image, causing him to avoid some and receive others". This is particularly common in press and advertising photography, where creators seek to control interpretation. Alternatively, titles can function as a "relay," where text and image exist in a complementary relationship. The unity of the message is realised at a higher level, that of the story or anecdote. Here, title and image work together to create meaning neither could achieve alone.

Creating Context: Titles can situate photographs within historical, cultural, or personal contexts. Contextual information may reference events, cultural phenomena, or artistic traditions that inform the creation or intended meaning of the photograph. For Roland Barthes, photographs have a unique relationship to time and reality. A photograph confirms "that the thing has been there", what Barthes called the photograph's noeme or "that-has-been" quality. Titles can enhance this quality by anchoring the image in temporal or spatial specificity, thereby providing a clear context for the viewer.

Establishing Artistic Voice: How photographers title their work contributes to their recognisable artistic voice. Consistent titling approaches—whether descriptive, poetic, or minimalist—become an integral part of a photographer's signature style. For instance, the American photographer Diane Arbus is known for her straightforward, descriptive titles, such as "Child with a toy hand grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C.," which contrast with the psychological complexity of her images.

Trends and Fashion in Photographic Titles

Photographers’ preferences for titling vary widely. Some enjoy crafting poetic or metaphorical titles, while others prefer the objectivity of straightforward descriptors. There is no universally “correct” way to title a photograph; the choice is shaped by the photographer’s goals, the nature of the work, and the intended audience. Like other aspects of photography, titling practices have evolved in tandem with shifting artistic sensibilities and cultural contexts.

The early 20th century favoured straightforward, descriptive titles, as seen in Lewis Hine's "Breaker Boys" (1911) or Dorothea Lange's "Migrant Mother" (1936). The mid-century shift toward more symbolic, psychological titles reflected broader currents in modern art, particularly the influence of Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism.

The 1970s witnessed an increased use of "Untitled" as photographers such as Garry Winogrand and Diane Arbus adopted a more open-ended approach to the relationship between image and meaning. Winogrand famously claimed to make photographs "to see what the world looks like in photographs," a philosophy reflected in his use of untitled works.

Contemporary digital photography has introduced new possibilities for titling. With photographs increasingly viewed on social media platforms, titles now function as searchable metadata and attention-grabbing headlines. Google Photos has even introduced AI-generated title suggestions for personal photographs, highlighting how technology continues to shape our relationship with image captioning.

Iconic Photographs and Their Titles

A helpful exercise is to review how other photographers title their images, whether in galleries or online platforms, and consider what resonates with you as both a creator and a viewer. Looking at the work of master photographers and their iconic photographs through history is a great way to begin:

Migrant Mother (1936) – Dorothea Lange

This evocative title encapsulates the hardship and resilience of a mother during the Great Depression. The photograph, taken in Nipomo, California, became a symbol of the era’s suffering and the plight of migrant workers.

The Falling Soldier (1936) – Robert Capa

The title directly references the moment captured: a soldier at the instant of death during the Spanish Civil War. Its starkness and immediacy have made it one of the most discussed and debated war photographs in history.

Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima (1945) – Joe Rosenthal

This title succinctly describes the event depicted: US Marines raising the American flag atop Mount Suribachi. The image and its title have come to symbolise American perseverance and sacrifice during World War II.

Raising a Flag over the Reichstag (1945) – Yevgeny Khaldei

Similarly, this title records a pivotal moment in World War II, as Soviet soldiers hoist their flag atop the Reichstag in Berlin, symbolising victory over Nazi Germany.

V-J Day in Times Square (1945) – Alfred Eisenstaedt

The title places the viewer at the scene of celebration at the end of World War II, as a sailor famously kisses a nurse in New York City’s Times Square.

The Hindenburg Disaster (1937) – Sam Shere

This descriptive title conveys the tragedy of the airship Hindenburg’s explosion. The image and its title have become shorthand for disaster and the end of an era in air travel.

The Soiling of Old Glory (1976) – Stanley Forman

The title refers to a violent moment during Boston’s busing crisis, where the American flag is used as a weapon. The phrase “soiling” in the title adds a layer of commentary to the image’s depiction of racial tension. Here’s an excellent NGN Magazine article about the historic image that makes for good reading.

Saigon Execution (1968) – Eddie Adams

This blunt title leaves no ambiguity about the content: the summary execution of a Viet Cong prisoner during the Vietnam War. Its directness adds to the photograph’s shock and historical impact.

Burning Monk (1963) – Malcolm Browne

The title refers to the self-immolation of Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc in protest against persecution in South Vietnam. The simplicity of the title belies the intensity of the event.

Tank Man (1989) – Jeff Widener

This title has become synonymous with the lone protester who stood in front of tanks during the Tiananmen Square protests. The anonymity of “Tank Man” amplifies the sense of individual defiance.

Afghan Girl (1984) – Steve McCurry

The title identifies the subject only by her nationality and gender. Yet, the image of Sharbat Gula’s piercing green eyes became one of the most recognised photographs in National Geographic’s history.

Lunch atop a Skyscraper (1932) – Charles Ebbets

The title captures the daring and everyday nature of construction workers eating lunch on a steel beam high above New York City, highlighting both the danger and camaraderie of the era.

The Roaring Lion (1941) – Yousuf Karsh

This portrait of Winston Churchill was titled after Churchill’s expression, which Karsh provoked by removing his cigar. The title has contributed to the enduring image of Churchill’s wartime persona.

Abbey Road (1969) – Iain Macmillan

While not a documentary image, the title of this photograph of the Beatles' album cover has become iconic, turning a simple street crossing into a cultural landmark.

Why These Titles Matter

These titles are impactful because they:

Anchor the image in a specific historical moment or event.

Evoke emotion or provoke thought through their phrasing.

Sometimes, add a layer of interpretation or commentary (e.g., “The Soiling of Old Glory”).

Become shorthand for the events or subjects depicted, often outlasting the original context.

In many cases, the title is as memorable as the image itself, shaping how the photograph is discussed, remembered, and understood for generations to come.

Practical Guidance for Titling Your Photographs

For photographers seeking to develop their approach to titling, consider these principles:

Match title to intent. Your titling approach should align with your photographic intentions. If your work aims to document reality, descriptive titles might be most appropriate. If you're creating conceptual or fine art photography, more interpretive titles could enhance your artistic vision. A well-chosen title can strengthen an image's impact by providing context, suggesting a narrative, or directing the viewer’s attention to specific aspects of the photograph. Conversely, overly elaborate or “flowery” titles can sometimes detract from the image or feel forced.

Complementing the Image: Good titles are generally seen as those that complement the work, offering relevant information or hints that enrich the viewer’s experience without overwhelming or limiting their interpretation. The goal is often to strike a balance, providing enough to intrigue or inform, but not so much that the image’s mystery or complexity is lost.

Personal and Organisational Factors: Some photographers use titles as a practical organisational tool, especially when managing extensive archives. Others use working titles or jot down impressions in a field log, later refining the title to reflect the final vision for the image.

Consider the audience and context. Where and how will your images be seen? The context in which the photograph will be viewed influences titling choices. Images destined for galleries, competitions, or publications may require more minimal, contemplative titling than those shared informally or kept for personal use. Social media favours engaging, headline-like titles—clickbait, essentially.

Experiment with different approaches—try various titling strategies to discover what resonates with your artistic vision:

Descriptive titles identify the subject, location, and perhaps date: "Autumn Reflections, Lake District, 2024"

One-word titles can be powerful in their simplicity: "Solitude," "Emergence," "Convergence"

Conceptual titles add interpretive layers: "The Space Between Thoughts," "Memory's Echo"

Numerical or coded systems create organisational frameworks without imposing meaning

Untitled works allow the image to speak without verbal mediation

The Smartphone Photographer's Approach to Titling

Smartphone photography has democratised image-making and transformed how we think about titles. While most smartphone images remain untitled in our camera rolls, they receive captions when shared on social media, a hybrid approach that separates private and public contexts.

The integration of AI capabilities into smartphone photography apps introduces new questions about authorship and meaning. When an algorithm suggests titles based on image recognition, whose interpretation is being privileged? This technological development invites us to consider more consciously the role titles play in our photographic practice.

For the smartphone photographer interested in developing a more thoughtful approach to titling, begin by considering your purpose. Are you documenting personal memories, creating artistic expressions, or building a portfolio? Different purposes may require different titling strategies.

Resources

This video, from Matt Day, goes into some depth about how to title your images, or not: “Giving your photo a title or description is often a chance to give the viewer context. You can guide them towards the interpretation or meaning of the photo. You can also just flat out tell them what the photo is about, leaving little to the imagination. But how can you do this within the photo itself? Is there an advantage to one method or the other? That’s what we’re discussing today.”

And this video, from Curiously, gives a fascinating perspective on titling practices in the art world, revealing image titles as a more recent development than you might think…

Hints & Tips for Effective Titles

Photographers select titles based on a combination of descriptive clarity, conceptual insight, organisational needs, and personal preference. The chosen title can shape the viewer’s engagement, provide context, or simply serve as a reference. Ultimately, the process is as individual as the photographer and their work. If you choose to title your work, these guidelines may help:

Choose a title that complements, rather than explains, your image. Avoid being overly literal; let the photograph do most of the storytelling.

Don’t hesitate to leave a work untitled if that suits your intent.

Set the right tone: Ensure your title matches the mood of your photograph, whether sad, funny, inspiring, or whimsical. When appropriate, use titles to add context, emotion, or intrigue.

Use active language: When appropriate, active verbs create more impact than static descriptions.

Be concise: Brevity often carries more power than verbosity.

Capture the essence: Focus on the central subject or feeling rather than peripheral details.

Consider multiple meanings: The best titles often work on several levels, rewarding deeper contemplation.

Avoid clichés: Overused phrases diminish impact and suggest less original thinking.

Test different options: If unsure, try several titles and see which resonates most strongly with your intentions for the image.

Give It a Try!

The practice of titling photographs exists in a productive tension between verbal and visual communication. Neither subordinate to the image nor separate from it, a well-chosen title creates a relationship with the photograph that enriches the viewer's experience.

Whether you choose descriptive clarity, poetic suggestion, or deliberate untitling, your approach reflects your philosophy about how images communicate and what role you wish to play in guiding—or not guiding—interpretation. Like the brief moment of a video game loading screen, a title provides an orientation —a momentary frame that influences but doesn't determine the experience that follows.

As you develop your photographic practice, consider titling not as an afterthought but as an integral aspect of your creative process—another tool for expressing your unique vision and connecting with viewers. The title you choose, or choose not to provide, shapes how your images will be encountered, interpreted, and remembered.

This week’s assignments…

For this week’s daily photos, your brief is to explore the many ways you can title your images, and take some time to consider how the title can influence the viewer’s first impressions of a photograph, can raise questions, tell a joke, or suggest an interpretation. The aim is not to feel that any particular style of title is right or wrong… simply to make the act of titling one that you think about as part of the photographic process.

Let’s see photographs and titles that work together with purpose—where the title (or its absence) contributes to the story or the emotions you mean to convey with your work.